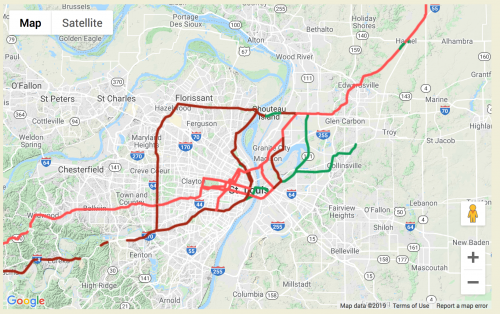

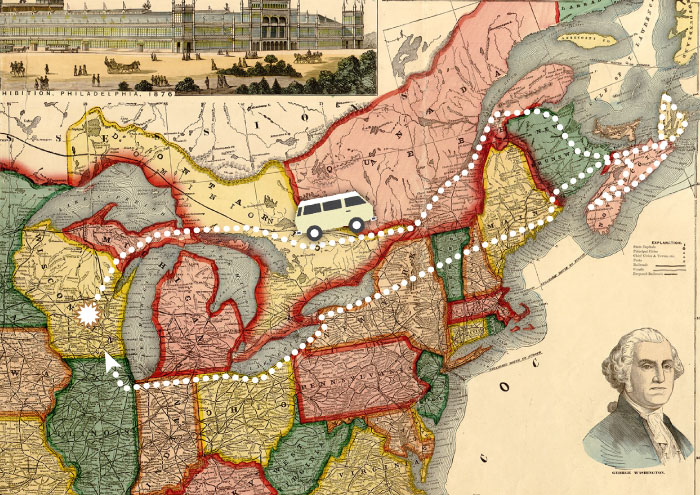

A three-week, 5000-mile road trip loosely following Route 66 from central Illinois to the Grand Canyon. With a few side trips …

We leave Beigeville Heights, Wisconsin, on a Friday morning and drive directly south, then turn to the southwest at Bloomington, Illinois, when we catch Route 66.

We leave Beigeville Heights, Wisconsin, on a Friday morning and drive directly south, then turn to the southwest at Bloomington, Illinois, when we catch Route 66.

Or, perhaps I should say “the nominal Route 66.” Safety improvements, replacement of bridges and railroad crossings, traffic congestion, all led to various bits and pieces of the designated Route being realigned numerous times since it was first established in 1926. So when one sets out to get one’s kicks on Route 66, one must ask, “When? The Route 66 of the 1930’s? Of the 1950’s? Before or after US Interstates 44 and 40 superseded the original Mother Road?”

In some places we find original concrete, in others the route is a barely-visible dirt path cutting across sagebrush country. Interstates 44 and 40 were in some places laid directly atop the old roadbed, in others were built miles away from the original route. In many places, the original Route 66 can now be seen closely paralleling the new Interstate as a frontage road.

Near Auburn, Illinois, we find a couple miles of an early brick-paved section of the old Mother Road.

Near Auburn, Illinois, we find a couple miles of an early brick-paved section of the old Mother Road.

In our hasty packing for the trip we have both forgotten adult beverages. Fortunately, it is in no short supply here in the town of Bourbon, Illinois.

Fill ‘er up, please!

In sleepy Spencer, Missouri, we find a place to fill up the van, too. Only 14.7 cents for a gallon of Ethyl!

Just a mile east of Cadillac Ranch in Amarillo, Texas, I spot my first of the legendary “Muffler Men,” this one now repurposed as “2nd Amendment Cowboy.” A plaque near his boots (complete with spurs) features the pertinent quote from the US Constitution.

We arrive at Tucumcari, New Mexico, and take a room at the classic Blue Swallow Motel, then cruise the original Route through town at sunset to check out some vintage and retro gas stations.

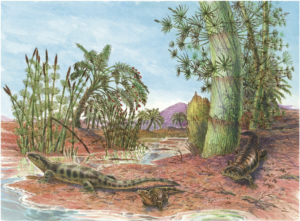

In Arizona we stop at Petrified Forest National Park. About 225 million years ago, trees that fell into rivers here were buried by volcanic ash sediments, and eventually fossilized in remarkably original appearance. Whole logs, some 40 feet long and 3 feet in diameter, now lie intact on the ground, their bark, knots, and even growth rings clearly visible.

In the parking lot, some Italian tourists express disappointment that the ‘fossilized forest’ is no longer comprised of standing trees …

In the parking lot, some Italian tourists express disappointment that the ‘fossilized forest’ is no longer comprised of standing trees …

One day I find this 1.5″ red-winged waspy thing eating dead bugs off the front of the Vanagon. Turns out it’s a Pepsis Wasp, whose sting is considered the most painful of all animal stings. It was described by one researcher as, “Blinding, fierce, shockingly electric. A running hair drier has been dropped into your bubble bath.” It won’t kill you, but it will likely be the longest three minutes of your life.

“They are also called tarantula hawks because the females hunt tarantulas (and other large spiders).”

“Standin’ on a corner in Winslow, Arizona,

Such a fine sight to see.

It’s a tired old man in a camper van,

Slowin’ down to find a place to pee.”

(with apologies to Glenn Frey)

We start the morning by driving a couple miles of the original-original Route 66 (now gravel). Then, on our journey to the Grand Canyon, we pause to visit the SECOND largest hole in the ground. Meteor Crater is 3/4 of a mile in diameter, over 500 feet deep, and was formed when a 150-foot meteorite struck at 29,000 MPH. Though not a National Park, this private, family-owned operation boasts perhaps one of the best such visitor centers/museums we’ve ever been to (and that’s quite a lot). Especially if you’re kind of a space-science nerd. We also highly recommend the one-hour guided rim walk; our local Navajo-Hopi guide really gave some great scientific and cultural context to this strange and spectacular place.

On our way through Flagstaff, Arizona, we finally learn the unfortunate source of those singular smoke columns we’ve been seeing on the horizon the last couple of days.

Quite by accident, we take one of the most beautiful scenic drives we’ve enjoyed so far on this trip, following State Route 89A down through Oak Creek Canyon, dropping nearly 2000 feet in 15 miles, into Sedona. We take a room for a few nights and enjoy day hikes, a ride on the Verde Canyon Railroad, and a sunset Jeep tour into the local hills.

Over breakfast on our final day here, another guest visiting from Phoenix complains that they have not seen any wildlife during their trip. I mention that last night while strolling back to the B&B with our Thai takeout boxes, we saw three coyotes cross the street, just a block from here. She clutches her purse and appears worried.

Eager to escape the utterly maddening traffic of Sedona, we climb back up Oak Creek Canyon to Flagstaff. We briefly cruise a few blocks of old Route 66 through downtown Flagstaff, then make a detour from the Mother Road. There are other roads to drive, and other sights to see, so we turn north toward the Grand Canyon, and are rewarded with a wonderful drive up through high desert ponderosa pine forests which open out to broad views of the San Francisco Peaks.

We enter Grand Canyon Village, claim our reserved campsite, then hurry to Trail View Point for our first glimpse over the South Rim.

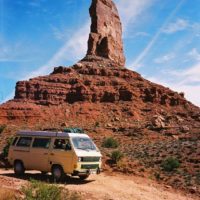

Over our many years of Westy traveling in North America, we’ve seen a lot of big stuff. We’ve dipped the wheels in both oceans; driven the 1500 miles around the world’s largest freshwater lake; crossed the Continental Divide countless times, sometimes as high as 11,000 feet; and camped below a prehistoric waterfall which was once five times the width of Niagara with ten times the flow of all the current rivers in the world combined.

Over our many years of Westy traveling in North America, we’ve seen a lot of big stuff. We’ve dipped the wheels in both oceans; driven the 1500 miles around the world’s largest freshwater lake; crossed the Continental Divide countless times, sometimes as high as 11,000 feet; and camped below a prehistoric waterfall which was once five times the width of Niagara with ten times the flow of all the current rivers in the world combined.

But nothing prepared me for the depth, the breadth, the utter scale of the Grand Canyon. For the first several minutes, I just stand there dizzily clutching the handrail like a dope, my eyes ratcheting in and out like a digital camera unable to auto-focus on its intended subject.

I finally recover, we drive to the next overlook, and it happens all over again.

Really, just a nearly incomprehensible magnitude of space …

For most of the peak season, the only way to see the western portion of the South Rim is via the National Park Service shuttle buses. They’re free, easy, they run every 10-15 minutes so you can hop on and off as you like, and they prevent the dangerous, frustrating, polluting traffic jams that used to plague the park. We ride the bus for much of our sightseeing the next day, and highly recommend this break from driving your own Bus.

The next day, we drive from Mather Campground to the east entrance along the Desert View Drive, then return the same way, stopping at all the viewpoints and other sites.

In the morning, we leave the South Rim via the same east entrance and head to the North Rim. This turns out to be one of the most dramatic and visually stunning scenic routes of this trip so far. Up the Little Colorado River gorge, then up the Marble Canyon flanked by the Vermilion Cliffs, over the soaring Navajo Bridge, then up the Kaibab Plateau to the North Rim Campground. Map.

The lodge and cabins are closed for the season, but the campground is open, so we settle in for a couple of 26-degree nights.

It took about a full day for my feeble brain to finally comprehend the immensity of the Grand Canyon’s South Rim, and upon arriving at the North Rim, I have to start all over again. In addition to being 1000 feet higher in elevation, the North Rim is also set back from the Colorado River 2-3 times further than the South Rim, with more spectacularly carved side canyons.

Also, a mere fraction of the crowds. Though still a fair number of narcissistic numbskulls (as seen above) who happily scamper beyond the designated barriers to take Instagram selfies posing on the precipice. Each year, of course, several fall to their deaths …

An enjoyable way to visit many of the scenic overlooks is a drive up Cape Royal and Point Imperial Roads, the latter of which offers a view from the highest point in all the Grand Canyon (elevation 8800′). So high, in fact, that the bag of Caramel & Cheddar Popcorn we purchased in eastern New Mexico (4000′) now spontaneously bursts open.

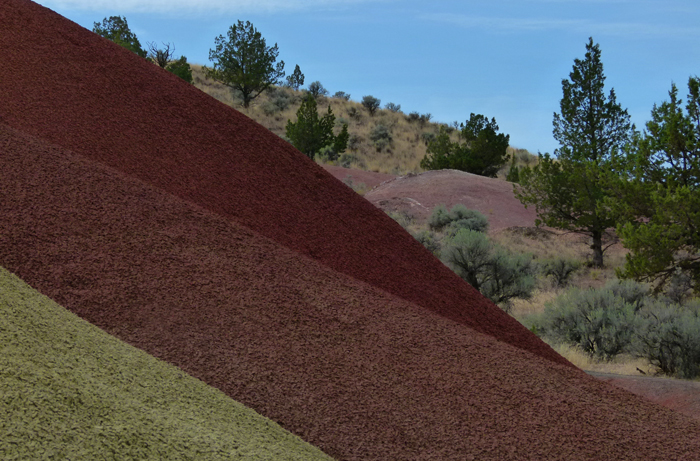

On our way from the North Rim to our next destination, we take a 30-mile backcountry byway on washboard gravel through the Vermilion Cliffs National Monument. The twisted and warped landscape here was formed when two tectonic plates collided 40 to 80 million years ago. Pretty quiet today.

On our way from the North Rim to our next destination, we take a 30-mile backcountry byway on washboard gravel through the Vermilion Cliffs National Monument. The twisted and warped landscape here was formed when two tectonic plates collided 40 to 80 million years ago. Pretty quiet today.

In Page, Arizona, we take a room where we can keep a close eye on our beloved vintage van. Or, perhaps the van is keeping an eye on us?

The next morning, we enjoy a guided cruise in Lake Powell to visit Lower Antelope Canyon.

Later, we tour Glen Canyon Dam, the controversial 700-foot-high concrete arch-gravity dam which holds back 27 million acre⋅ft of water to form Lake Powell, one of the largest man-made reservoirs in the U.S.. The hydro-electric generators also produce 5 billion kilowatt hours each year, or enough to power 330,000 homes at any given moment.

We depart in the morning for Bryce Canyon National Park, take a site at Sunset Campground, then spend the rest of the day tooling along the main park road enjoying all the scenic overlooks and viewpoints.

The drive northeastward from Bryce Canyon on US 12 starts off scenic enough but mile by mile, as we continue through Cannonville, Escalante, and Boulder, the country grows increasingly dramatic. By the time we swing eastward at Torrey and enter Capitol Reef National Park, the jaw-dropping bluffs and cliffs are ablaze in gold and crimson as sunset approaches.

We discover the campground at Fruita, Utah, has several cancellations due to the sudden cold snap, so we take a site and settle in. After a day of motoring across the rocky, barren land of the Kaiparowits Plateau, we find the tiny former community at the junction of the Fremont River and Sulphur Creek a veritable oasis. Now preserved by the NPS for its historical value, the small farm and orchard complex was a small, isolated community of largely self-sufficient Mormon farmers and other frontier folk. The orchards of her residents prospered, offering apples, apricots, cherries, peaches, pears, and plums, and by 1900 Fruita was known as “the Eden of Wayne County.”

The broken and jumbled landscape here is the result of a hundred-mile long warp in the Earth’s crust that formed between 50-70 million years ago, along an ancient buried fault line. Today, the rock layers in Capitol Reef reveal ancient environments as varied as rivers and swamps, deserts, and inland seas, recording nearly 200 million years of geologic history.

In the morning we follow State Hwy 24 along the Fremont River as it tumbles down the rocky canyon. Like so many other routes in this area, the 40 miles to Hanksville, Utah, is a dramatic and stunning drive.

We plan to begin our eastward swing here, cutting across the midsections of Utah and Colorado and eventually homeward. But a pair of winter storms is sweeping down on the region, predicted to drop 4-10″ of snow before we’re able to cross the central Rockies. So, instead we scoot south from here to Albuquerque to steer clear of the storms, rejoining Route 66 and retracing our route along I-40.

We have clear sailing with a favorable tailwind until Santa Rosa, New Mexico, when the expanding gray storm front swells to overtake us. We are soon surrounded by strange twisting wraiths of freezing fog, pelted by snow-hail, and the Westy windshield becomes glazed with icy sleet. A sense of impending danger descends, so we pull off the highway, take one of the last available rooms at Tucumcari, and order a pizza. Throughout the night, we hear almost constant sirens on the nearby Interstate …

The next morning, under clear and cold skies, we resume our homeward drive. Every few miles are marked by a car stuck in a culvert, or an overturned pickup, or any number of crashed semi-trucks. In a couple places, there is nothing left but a rectangle of black and charred pavement and a road crew scooping up a smoldering pile of twisted steel.

We are fortunate in so many ways, and carefully thread our way home along the Mother Road …

Needless to say, this has gobbled up lots of farmland, hundreds of homes, highways, railroads, and other infrastructure, and is threatening to consume the city of Devils Lake. In recent years, more than 350 million in federal dollars have been spent to relocate people, raise roads, and build levees, and everywhere you look there are giant earthmovers and great piles of rip-rap. Side roads turn off and promptly disappear beneath the waves, standing forests of dead and blackened trees line the shallows, and abandoned farms poke up out of the water.

Needless to say, this has gobbled up lots of farmland, hundreds of homes, highways, railroads, and other infrastructure, and is threatening to consume the city of Devils Lake. In recent years, more than 350 million in federal dollars have been spent to relocate people, raise roads, and build levees, and everywhere you look there are giant earthmovers and great piles of rip-rap. Side roads turn off and promptly disappear beneath the waves, standing forests of dead and blackened trees line the shallows, and abandoned farms poke up out of the water.