Day 6 Grand Marais, Minnesota

Our wake-up call this morning comes courtesy of Jake, genius boy-inventor of the noisy “Jake Brake”, standard equipment on the rumbling logging trucks on the highway just outside our front door. We arise early and have breakfast in a cafe overlooking the small harbor, and see no sign of the Grand Marais—or Big Swamp.

Before hitting the road, we stop at a convenience store for road snacks. It’s a briskly cold morning, so when Lorie goes inside I turn on the Westy’s seldom used diesel-fueled auxiliary heater to warm things up while I check the Westy’s tire pressures. Lorie returns with Twinkies and chocolate milk just in time to find the van, and me, engulfed in white smoke clouds of cumulonimbus proportions. I quickly reach inside the cab to switch off the heater, and when I emerge from the swirling billows of smoke I see Lorie halted, petrified, a safe distance away while other patrons nervously duck or crouch warily behind their vehicles. I finally manage to coax Lorie into the van, and I cheerfully wave and motor away, leaving behind only a lingering odor and some bewildered townsfolk.

Before hitting the road, we stop at a convenience store for road snacks. It’s a briskly cold morning, so when Lorie goes inside I turn on the Westy’s seldom used diesel-fueled auxiliary heater to warm things up while I check the Westy’s tire pressures. Lorie returns with Twinkies and chocolate milk just in time to find the van, and me, engulfed in white smoke clouds of cumulonimbus proportions. I quickly reach inside the cab to switch off the heater, and when I emerge from the swirling billows of smoke I see Lorie halted, petrified, a safe distance away while other patrons nervously duck or crouch warily behind their vehicles. I finally manage to coax Lorie into the van, and I cheerfully wave and motor away, leaving behind only a lingering odor and some bewildered townsfolk.

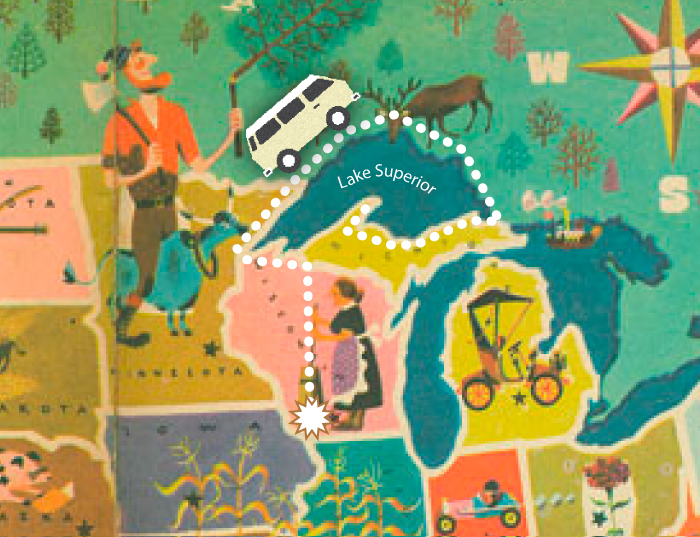

We follow the historic Gunflint Trail out of Grand Marais, up into the wild country of extreme northeast Minnesota. Probably first blazed by Archaic native peoples more than 5,000 years ago, the Gunflint was later used as a trade route by Ojibwe, Voyageurs, and fur trappers. Even today it is one of the primary gateways to the backcountry of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area, a remote region along the Canadian border boasting probably half of Minnesota’s famed 10,000 lakes. Ancient pictographs can still be found on rock faces and cliffs along the lakes in this region, and trapping and trading flourished here through the 19th century.

Laurentian Divide: “Water at this point flows northward into Canada’s Hudson Bay watershed and eastward into the Saint Lawrence watershed.”

Hundreds of hikers and paddlers were camped in the Boundary Waters, and even those with weather radios had nowhere to hide when the powerful straightline winds blasted into their camps. Search-and-rescue floatplanes and helicopters spent days evacuating the injured. Despite the awesome destruction, the Wilderness Area has begun its recovery, with new areas opened up to deer and wolf populations, and young seedlings already struggling upward among the fallen bodies of their parents.

Rejoining Hwy 61, we continue northward and cross into Canada just north of Grand Portage, MN, then drive nearly to Thunder Bay, Ontario. It is almost dark when we arrive at Kakabeka Falls Provincial Park and camp for the night.