Some additional photos from Camp Westfalia’s “Southwest by Westy” travelogue >>

- HOME

- Happy Camping

- A Westfalia Tour

- The Kitchen

- Instant Eats: Breakfast

- Planning a Roadtrip, Part 1

- Planning a Roadtrip, Part 2

- Packing for the Road

- The Routine

- Essential Apps for Van-Travel

- Making the Most of Stay-at-Home Orders, for Van-Campers

- 10 Great Van Camping Accessories

- Using RV Levelers

- Staying Cool On Summer Road Trips

- Winter Van Camping

- Van-Camping with Your Dog

- Journeys

- Workshop

- Product Reviews

- Vanagon Workshop Manuals

- Westfalia Closet Organizer

- Dash Car Fan

- “Little Buddy” Propane Heater

- GSI Outdoors Bugaboo Folding Camp Fry Pan

- Pioneer MVH-X580BS Stereo

- Collapsible Gray Water Container

- Thermos Sipp Travel Mug

- Sports Imports Folding Cup & Beverage Holder

- Audew 150PSI Compact Air Compressor

- ASUS Eee Pad Transformer Mobile Tablet

- Samsung Galaxy Note Pro Tablet

- ZeroLemon SolarJuice Dual-USB Portable Charger

- Galleries

- Resources

- Shop

- Blog

- About

Archive for Southwest

Day 13: Zion National Park, Utah

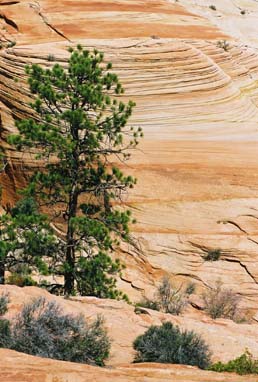

We sleep in late today and enjoy a leisurely breakfast in camp. I take Lorie into nearby Springdale for shopping, then drive back up the Zion–Mt. Carmel Highway toward the east park entrance. Parking on a roadside turnout, I hike up into the slickrock hills to explore these beautifully sculpted and wind-weathered forms. Countless layers of sand deposited on an ancient sea-bed 240 million years ago have since hardened into stone. When the oceans receded, these landforms were exposed to the wind and flowing and freezing waters, and even today continue to be carved and shaped into their varied and evocative forms.

We sleep in late today and enjoy a leisurely breakfast in camp. I take Lorie into nearby Springdale for shopping, then drive back up the Zion–Mt. Carmel Highway toward the east park entrance. Parking on a roadside turnout, I hike up into the slickrock hills to explore these beautifully sculpted and wind-weathered forms. Countless layers of sand deposited on an ancient sea-bed 240 million years ago have since hardened into stone. When the oceans receded, these landforms were exposed to the wind and flowing and freezing waters, and even today continue to be carved and shaped into their varied and evocative forms.

To walk in this quiet and alien landscape is to visit another realm, and to glimpse some measure of what can result from miniscule and imperceptible changes multiplied over countless eons. Nothing can be as ‘old as the hills’ when compared to these ancient and weathered bones of the earth lying exposed to daylight.

To walk in this quiet and alien landscape is to visit another realm, and to glimpse some measure of what can result from miniscule and imperceptible changes multiplied over countless eons. Nothing can be as ‘old as the hills’ when compared to these ancient and weathered bones of the earth lying exposed to daylight.

The drive back down into the canyon is just as awe-inspiring as two days ago when we saw it for the first time. It is plain to see why both native peoples and later Mormon settlers each applied their respective spiritual and religious names to this place, for it truly inspires thoughts of a world beyond this one.

I meet Lorie near the visitor center to enjoy our final sunset in this beautiful place. Tomorrow we will begin our return journey north, then eastward to our home in the Midwest. After the last fading rays of the sun depart from the canyon wall, we enjoy gyros and beer in a small cafe, then begin our walk back through the darkening park grounds to our camp. The narrow belt of stars overhead seems all the brighter when framed on two sides by the black and looming hulks of the canyon walls, and as I watch, a bright new star moves into view.

Appearing from behind one rim of the canyon, this celestial body—larger and brighter than any other—moves with an eerie and determined grace across the starfield. Before we can utter a surprised word to one another, a second and equally bright point of light appears, following at a steady speed close behind the first. Together and in tandem, this pair of bright stars tracks smoothly across the night sky on a silent and disconcertingly straight course.

Appearing from behind one rim of the canyon, this celestial body—larger and brighter than any other—moves with an eerie and determined grace across the starfield. Before we can utter a surprised word to one another, a second and equally bright point of light appears, following at a steady speed close behind the first. Together and in tandem, this pair of bright stars tracks smoothly across the night sky on a silent and disconcertingly straight course.

Within a moment, I recall hearing a radio report earlier that day about the space shuttle Atlantis having undocked from the orbiting International Space Station and pulling away to begin its return to Earth, and I realize we must now be witnessing this super-aerial ballet. The pair tracks across the dark sky—leading us from West to East—and I briefly ponder their flight, and our own impending return to our home in the East.

As first one point of light disappears behind the opposite canyon wall, followed a moment later by the other, I can only hope that our return journey from these high mountains to the lowlands of our home does not resemble too closely the descent and fiery re-entry that await those brave astronauts. Though finally touching down in our driveway and familiar bed will be no less sweet …

Notes for the Vanageek

Notes for the Vanageek

- Total Trip Mileage: 4781 Miles

- Total Fuel Used: 184 Gallons

- Overall Trip Average: 26 MPG

- Oil Consumption: 3 Qts.

Day 12: Zion National Park, Utah

Can you see the rock-climbers about two-thirds of the way up the wall? Of course not. The cliffs are too large and the pixels too few. These cliffs are 250-350 stories tall–two or three Sears Towers could be stacked atop one another and still not reach the canyon rim.

After vacating our cabin and driving thru the lower canyon to nearby Springdale for breakfast, we return to the park to choose a campsite. Then it’s off to the museum for a bit of geological and human history and a beautiful introductory film of Zion National Park.

But to truly appreciate the grandeur of Zion one must actually see it, and the National Park Service shuttle busses make it easy, even with 2.5 million annual visitors. If riding a shuttle bus sounds like a hassle, consider instead the alternative of sitting immobilized in the fume-laden, bumper-to-bumper traffic snarls that were common before the new bus system. Not the most enjoyable way to experience the great outdoors.

Instead, as the bus driver points out noteworthy sites of interest, we ride in air-conditioned comfort and enjoy the views. When something sounds intriguing we simply hop off at the next stop and go hiking or snap some photos or dabble our toes in the river before catching another bus, another of which comes along every six minutes.

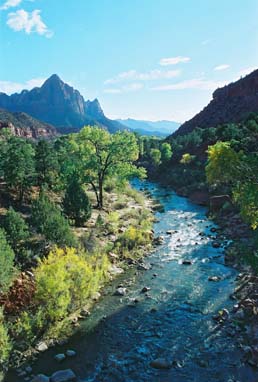

The spectacular Zion Canyon was carved by the North Fork of the Virgin River, which, over millions of years, has carried away several thousand feet of rock that once lay above the highest layers visible today. The river is still excavating today, eroding the shale, undermining the overlaying sandstone and causing it to collapse, widening the canyon. Occasional landslides and great house-sized chunks of sandstone pried from the walls by the repeatedly freezing-and-thawing water continue to widen the canyon and form rubble heaps at the base of the walls. Darkness falls quickly here in the canyon. The valley is so deep and narrow that the riverbanks receive only about four hours of direct sunlight each day, before the sun vacates that narrow swath of sky overhead and disappears behind the canyon wall. We ride the bus to the visitor center, then stroll back along the Virgin River to camp for a late dinner.

The spectacular Zion Canyon was carved by the North Fork of the Virgin River, which, over millions of years, has carried away several thousand feet of rock that once lay above the highest layers visible today. The river is still excavating today, eroding the shale, undermining the overlaying sandstone and causing it to collapse, widening the canyon. Occasional landslides and great house-sized chunks of sandstone pried from the walls by the repeatedly freezing-and-thawing water continue to widen the canyon and form rubble heaps at the base of the walls. Darkness falls quickly here in the canyon. The valley is so deep and narrow that the riverbanks receive only about four hours of direct sunlight each day, before the sun vacates that narrow swath of sky overhead and disappears behind the canyon wall. We ride the bus to the visitor center, then stroll back along the Virgin River to camp for a late dinner.

Day 11: Bryce Canyon National Park, Utah

Cold night in the Westy: 26 degrees F. Thank goodness for long underwear, wool socks, and down sleeping bags. We arise early to catch the sunrise in the Canyon, but the van stubbornly refuses to start, even after a couple of rolling push-starts. Our new friends from next door kindly offer to pull-start us using their Westy and a borrowed tow rope, and he hitches us up. It must be quite a curious and comical scene for the onlooking RV crowd: an old air-cooled Westy yanking a coughing, sputtering diesel Westy around the campground loop. Two laps and she finally fires-up. As always, she will start and run perfectly the rest of the day.

After a quick breakfast we drive the mesa loop road overlooking Bryce Canyon in the early morning sun. When the ocean retreated it left behind layers of sediments thousands of feet thick here, and these now form the oldest, lowest layers of gray-brown rocks at Bryce Canyon.

After a quick breakfast we drive the mesa loop road overlooking Bryce Canyon in the early morning sun. When the ocean retreated it left behind layers of sediments thousands of feet thick here, and these now form the oldest, lowest layers of gray-brown rocks at Bryce Canyon.

Later, streams and rivers descending from surrounding highlands deposited additional layers of iron-rich sediments atop the first. These later deposits became the higher, reddish-pink stone from which the beautiful spires, fins, and hoodoos of Bryce Canyon were sculpted.

Once a cattle ranch owned for many years by Ebenezer Bryce, and known locally as Bryce’s Canyon, this place became a National Monument only in 1923. Years later Old Man Bryce was asked what it was like to have lived and ranched in such a ruggedly beautiful and spectacularly scenic landscape. “Well,” he replied, “it’s a helluva place to lose a cow.”

A scenic drive along the Sevier River finally brings us to the gates of Zion National Park. The next 10 miles offer some of the most awe-inspiring views of nature in her most rugged and beautiful forms, as we make a dizzying descent into the canyon to the Virgin River far below.

A scenic drive along the Sevier River finally brings us to the gates of Zion National Park. The next 10 miles offer some of the most awe-inspiring views of nature in her most rugged and beautiful forms, as we make a dizzying descent into the canyon to the Virgin River far below.

Natural forces similar to those which formed Bryce Canyon have make the park a truly unique landscape of sculptured canyons and soaring cliffs.

We have reserved a night in the Zion Lodge mountain cabins, scattered on the grassy grounds along the base of the 3000-foot canyon cliffs, and we gratefully sprawl on the soft beds for a while before showering and dressing for dinner.

We have reserved a night in the Zion Lodge mountain cabins, scattered on the grassy grounds along the base of the 3000-foot canyon cliffs, and we gratefully sprawl on the soft beds for a while before showering and dressing for dinner.

In the Lodge we take in a slide presentation—“Lizards and Snakes and Frogs, Oh My!”—to learn about the local creepie-crawlies, then adjourn to the upstairs dining room for a fine dinner and views of the canyon walls and river as the sun sets.

Day 10: Goblin Valley State Park, Utah

In the morning we enter Utah’s nearby Goblin Valley State Park, the centerpiece of which is a 20-acre shallow valley inhabited by thousands of eerie, vaguely humanoid sandstone forms called ‘hoodoos’, silent and motionless. Perhaps merely the result of a missed breakfast and resulting low blood-sugar, a walk through this strange valley–seemingly suspended in time–instills in us a sense of great, impending activity, as though dark magic has frozen this army of warriors in the midst of heated battle. But for how long? We hurry out of that place, before these legions of silent soldiers can spring to life, to defend the walls of their stony fortress.

In the morning we enter Utah’s nearby Goblin Valley State Park, the centerpiece of which is a 20-acre shallow valley inhabited by thousands of eerie, vaguely humanoid sandstone forms called ‘hoodoos’, silent and motionless. Perhaps merely the result of a missed breakfast and resulting low blood-sugar, a walk through this strange valley–seemingly suspended in time–instills in us a sense of great, impending activity, as though dark magic has frozen this army of warriors in the midst of heated battle. But for how long? We hurry out of that place, before these legions of silent soldiers can spring to life, to defend the walls of their stony fortress.

We return to the highway and continue our journey westward. Entering Dixie National Forest, we climb a beautiful, steep ascent to 9200’ASL through golden aspen-covered hills and mountains, then descend into Boulder, UT. Another 75 miles of spectacular canyon and mesa-top driving brings us to the gates of Bryce Canyon National Park.

We return to the highway and continue our journey westward. Entering Dixie National Forest, we climb a beautiful, steep ascent to 9200’ASL through golden aspen-covered hills and mountains, then descend into Boulder, UT. Another 75 miles of spectacular canyon and mesa-top driving brings us to the gates of Bryce Canyon National Park.

Another benefit of travelling by Westy is all the wonderful people one meets on such a roadtrip. We will see a total of 27 other Westies during our 14-day sojourn—from old air-cooled Busses to the latest EuroVans—and most drivers happily greet us with a beep or a wave or a flash of the lights. Today we find a campsite next to a wonderful couple from nearby St. George, camped in their 1983 Vanagon Westfalia—the last of the air-cooled—and accompany them to Bryce Lodge for a presentation on forest fires before retiring for the night.

Day 9: Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado

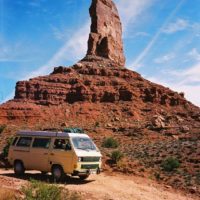

Heading out of Mesa Verde NP in an early start, we narrowly miss the Four Corners (an arbitrary intersection of lines on a map, really, of significance only to armchair cartographers). Our route turns northward into Utah and we come to Valley of the Gods.

Heading out of Mesa Verde NP in an early start, we narrowly miss the Four Corners (an arbitrary intersection of lines on a map, really, of significance only to armchair cartographers). Our route turns northward into Utah and we come to Valley of the Gods.

A 17-mile road loops off Hwy. 160, leading one through a stark landscape of redrock spires, fins, towers, and flat-topped mesas. There is little interpretive information regarding this mystical place, but it is easy to see how the minds of early native Americans were transported to unearthly realms by the otherworldly character of Valley of the Gods. NOTE: This loop road is very rough in places, and can be challenging to drive. Assuming no stops for hikes or further exploration, allot at least two hours for the driving tour.

Perhaps the single greatest attribute of travelling by Westy is its versatility. One moment it is a fuel-efficient transportation device, cruising across the continent at (nearly) the speed limit, the next it is a cozy cabin in the woods with roomy sleeping accommodations. Later, it is a nimble off-road vehicle, crawling about over rocky terrain, venturing off the beaten track where RV’s fear to tread.

We return to the pavement and continue northward on Hwy. 160. Within a mile or so the road appears to run smack into a 1000’ redrock canyon wall, but instead begins a series of 12% grades and switchbacks which claw their way to the rim of Cedar Mesa above. Called the Moki Dugway, the roadway was still under construction or major maintenance when we visited in October of 2002, so several sections were unpaved or deeply rutted. Guard rails are seldom seen. Only your nerves of steel, attention span, and white knuckles stand between you and the wild blue yonder. Cresting the lip of the canyon we make speed across the vast plateau thru high-desert terrain of sandstone, juniper, and sage.

We return to the pavement and continue northward on Hwy. 160. Within a mile or so the road appears to run smack into a 1000’ redrock canyon wall, but instead begins a series of 12% grades and switchbacks which claw their way to the rim of Cedar Mesa above. Called the Moki Dugway, the roadway was still under construction or major maintenance when we visited in October of 2002, so several sections were unpaved or deeply rutted. Guard rails are seldom seen. Only your nerves of steel, attention span, and white knuckles stand between you and the wild blue yonder. Cresting the lip of the canyon we make speed across the vast plateau thru high-desert terrain of sandstone, juniper, and sage.

Lake Powell is comprised of 162,700 acres of water impounded by the infamous Glen Canyon Dam. Completed in 1966, it took 17 years for Lake Powell to completely fill for the first time, flooding 186 miles of the Colorado River and creating 2000 miles of shoreline–more than the entire west coast. Numerous natural and archeological treasures were lost forever when the flood gates closed, and the controversial dam is regarded by many as the birthplace of the modern environmental movement.

Lake Powell is comprised of 162,700 acres of water impounded by the infamous Glen Canyon Dam. Completed in 1966, it took 17 years for Lake Powell to completely fill for the first time, flooding 186 miles of the Colorado River and creating 2000 miles of shoreline–more than the entire west coast. Numerous natural and archeological treasures were lost forever when the flood gates closed, and the controversial dam is regarded by many as the birthplace of the modern environmental movement.

Home on the range. The Bureau of Land Management oversees 264 million acres of federal lands, mostly in the western states, owned by all US citizens. Open for a variety of uses–mining, wildlife management, recreation–visitors can usually utilize this land free of charge. If camping, previously-used sites should be utilized, or apply No-Trace camping rules: take nothing but photos, leave only footprints.

Cost to enjoy a crackling campfire in our secluded spot overlooking a small canyon: zero.

Gazing slack-jawed at a million stars wheeling overhead in the blackest of skies: zip.

Bedtime serenade by distant and harmonious coyotes: zilch.

Sipping a steaming mug of fresh-brewed coffee while watching the sun rise on the prairie: priceless.

Day 7: Durango, Colorado

It’s only about a half-hour’s drive through high desert country from Durango to Mesa Verde National Park, so it is mid-morning when we arrive at the gate. We quickly choose a campsite and then head farther into the park for lunch at the Far View restaurant, then to the nearby visitor center for maps and information. The large namesake mesa of the park is shaped rather like an outstretched human hand when viewed from above, with palm facing downward and fingers splayed out. A park road loops out onto several of these ‘fingers’ of high, flat ground, and offers views down into the narrow canyons between them.

It’s only about a half-hour’s drive through high desert country from Durango to Mesa Verde National Park, so it is mid-morning when we arrive at the gate. We quickly choose a campsite and then head farther into the park for lunch at the Far View restaurant, then to the nearby visitor center for maps and information. The large namesake mesa of the park is shaped rather like an outstretched human hand when viewed from above, with palm facing downward and fingers splayed out. A park road loops out onto several of these ‘fingers’ of high, flat ground, and offers views down into the narrow canyons between them.

It is on these mesa tops that the early Anasazi settlers–now referred to as the Ancestral Puebloans– built their homes and raised their crops of corn, beans, and squash. A drive along the Mesa Top Loop Road offers ample opportunity to visit several partially excavated Puebloan dwelling sites atop the mesa. Conveniently arranged in chronological order as they developed through time, the sites represent different eras in domestic development of these ancestors to today’s Pueblo Indians. Around a.d. 750, they began settling into small villages, the Spanish word for which is “pueblo”. Construction techniques of these village houses evolved over time, using the same fundamental materials—wood poles, natural or cut stone, adobe, and even plaster—but in a changing variety of methods.

Upon returning to camp, we meet a couple of women travelling in their 1987 Vanagon Westfalia, in the midst of a 9-month roadtrip. After the requisite greetings and chatter about our vans and our trips, they ask if our van has a name. We admit that she does not, but promise to start thinking about it.

Day 8: Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado

Until recently, anthropologists have believed that prior to the introduction of horses by Spanish explorers, early Anasazi cliff-dwellers were limited to foot travel for hunting, trading, and even major societal migrations. But the recent discovery of a series of cave paintings depicting a far more elegant and convenient mode of transport indicates that one lesser-known splinter group of these ancient people was far more advanced and mobile than previously thought. Scientists are referring to this obscure cult, who evidently travelled in great comfort and style, as the Vanasazi.

This morning we roll down the campground road and pop the clutch to start her engine, then continue on to the visitor’s center, where we purchase tickets for a couple of guided tours to the famous cliff dwellings, then to the Chapin Mesa Museum. Here, we learn that the name often applied to these nearly-gone people, the Anasazi, has been variously translated as “the old ones” and “our ancient enemy”. Considering our Vanagon’s advanced age, and her recent troublesome behavior, the modified moniker “Vanasazi” seems only appropriate. (Once home, I will discover that a short-circuit in the glow-plug system has burned out the plugs. With the replacement of her glow plugs and relay, Vanasazi soon returned to her usual dependability, but the name has stuck.)

Entry to Balcony House requires us to descend a 100’-long staircase into the canyon to a place just below the dwelling, then climb a 32’ ladder to the first balcony. Stooping down to crawl on hands and knees through a narrow tunnel, we finally stand up in the main balcony. The view from here is breathtaking, with a beautiful vista of the canyon spread out below us.

Entry to Balcony House requires us to descend a 100’-long staircase into the canyon to a place just below the dwelling, then climb a 32’ ladder to the first balcony. Stooping down to crawl on hands and knees through a narrow tunnel, we finally stand up in the main balcony. The view from here is breathtaking, with a beautiful vista of the canyon spread out below us.

What now appears as only a series of half-fallen walls and small piles of rubble was once a densely inhabited and thriving village, probably resembling a modern apartment complex. The small doorways in the cliff dwellings were likely built that way to provide protection from the cold winds which are common for half the year, and were probably covered with 1”-thick sandstone slabs. During the summer months, the inhabitants perhaps placed willow mats, skins, or hides over the doorways.

What now appears as only a series of half-fallen walls and small piles of rubble was once a densely inhabited and thriving village, probably resembling a modern apartment complex. The small doorways in the cliff dwellings were likely built that way to provide protection from the cold winds which are common for half the year, and were probably covered with 1”-thick sandstone slabs. During the summer months, the inhabitants perhaps placed willow mats, skins, or hides over the doorways.

It is not known for certain why the Puebloans built these cliff dwellings; perhaps for safety from enemies, perhaps to secure the dwindling water sources found at the cliffside springs. Perhaps it was a religious belief which compelled them to seek a home closer to the folds of the earth, from which they believe all humankind sprang.

Perhaps the most evocative feature of these villages was the “kiva”, an underground ceremonial chamber which served as the religious center or shrine of each family unit. This circular subterranean room was covered over with timbers and adobe paving, and accessed via a ladder. This doorway also served as the chimney for the fire which burned within. The native inhabitants of Mesa Verde continued to build these kivas, and even developed more elaborate variations, when they left the mesa tops and began building their homes in the many natural stone alcoves in the canyon walls below, around a.d. 1200.

Perhaps the most evocative feature of these villages was the “kiva”, an underground ceremonial chamber which served as the religious center or shrine of each family unit. This circular subterranean room was covered over with timbers and adobe paving, and accessed via a ladder. This doorway also served as the chimney for the fire which burned within. The native inhabitants of Mesa Verde continued to build these kivas, and even developed more elaborate variations, when they left the mesa tops and began building their homes in the many natural stone alcoves in the canyon walls below, around a.d. 1200.

Within three generations, a severe drought struck the region, drying up springs, decimating crops, and lasting over 20 years. People began abandoning one site after another, migrating to better lands to the southeast, and by a.d. 1300 all 600 cliff dwellings stood empty and silent, bearing mute testimony to the lives of those who once planted and hunted, danced and worshipped, lived and died here.

Day 6: Durango, Colorado

One of the highlights of a visit to historic Durango, CO, is the Durango & Silverton Narrow Gauge Railroad. Built in 1881 to haul silver and gold ore out of the San Juan Mountains, it is estimated that over $300 million in precious metals was transported over the route. Today, the ore is gone and the mines gone bust, but there is still plenty of loose change to be found in the pockets of tourists, and a few hundred thousand passengers ride the old rails each year.

One of the highlights of a visit to historic Durango, CO, is the Durango & Silverton Narrow Gauge Railroad. Built in 1881 to haul silver and gold ore out of the San Juan Mountains, it is estimated that over $300 million in precious metals was transported over the route. Today, the ore is gone and the mines gone bust, but there is still plenty of loose change to be found in the pockets of tourists, and a few hundred thousand passengers ride the old rails each year.

Happily, the elegant old downtown hotel we unwittingly chose last night—the General Palmer—was built and operated by the same magnate who owned the original rail line, and is located not 100 paces from the D&SNGRR depot. Beside the platform, the old steam locomotive puffs and hisses, blowing smoke, and we board the restored passenger coaches to take our seats.

Now called the D&SNGRR, the railroad continues to provide year-round service operating a historical train with rolling stock indigenous to the line. The coal-fired and steam-operated locomotives are 1923-25 vintage and are maintained in original condition.

With a couple blasts of the whistle and a jerk of the couplers, the train pulls out of the station promptly at 8:15am and we make our way out of Durango. The rails soon converge with the Animas River and we begin to follow it northward toward Silverton. Sometimes skirting its banks, or crossing it on bridges high and low, or winding our way along narrow canyon ledges far above the roaring water, the Animas will be our near-constant companion for the 45-mile, 2800-foot ascent to the old silver mining town.

We make several stops along the way; some to pickup passengers at tiny stations in the forest, some to take on water from large tanks, some for no apparent reason whatsoever. After the third unexplained stop somewhere in the middle of the woods, the conductor comes through our car to apologize; the locomotive is having a bit of trouble today and must pause periodically to build up a head of steam for the next climb. I think of the sweaty locomotive fireman who must hand-shovel nearly six tons of coal into the firebox, to boil almost 10,000 gallons of water for the round trip.

We make several stops along the way; some to pickup passengers at tiny stations in the forest, some to take on water from large tanks, some for no apparent reason whatsoever. After the third unexplained stop somewhere in the middle of the woods, the conductor comes through our car to apologize; the locomotive is having a bit of trouble today and must pause periodically to build up a head of steam for the next climb. I think of the sweaty locomotive fireman who must hand-shovel nearly six tons of coal into the firebox, to boil almost 10,000 gallons of water for the round trip.

Strolling the station platform after our rail excursion, I am struck by several similarities between a 1983 diesel Westy and a 1923 Mikado steam locomotive. Both produce clouds of smoke when departing; pause to take on water before attempting to climb steep grades; generally depart on time but arrive late; elicit smiles and waves from small children and other passersby, with requests to hear the horn.

After a few more such stops we finally arrive in the historic town of Silverton, CO, nestled in a green and rocky mountain valley, and we quickly disembark for lunch. After cheeseburgers in a local diner, Lorie heads off for shopping in the restored downtown district while I seek out the original and unvarnished fringes of this rough former frontier town.

Returning to Durango in late afternoon, we do a bit of shopping in the historic downtown district, enjoy perhaps the best Mexican dinner ever at Francisco’s Restaurante Y Cantina on Main Ave., then retire to our room at the General Palmer.

Day 5: Great Sand Dunes National Monument, Colorado

The Westy gives us trouble this morning, but of another kind; repeated attempts to start her fail to produce anything but clouds of smoke. Finally rolling silently out of our campsite and down the hill, we pop the clutch and the engine fires right up. Once warmed-up, the van performs flawlessly the rest of the day–and will continue to do so every day after that–except requiring a similar rolling start most mornings. This is usually little more than a persistant inconvenience, but in those morning locations without a suitable hill, an old-fashioned manual push-start is called for, which is a discouraging way to achieve one’s daily workout.

We leave Great Sand Dunes about noon, again swing west on Hwy. 160, and enjoy lunch at a picnic table beneath cottonwood trees in a grocery-store parking lot in Alamosa. In the branches overhead, raucous and hungry crows await our leftovers. We leave town and get a running start for our climb to the Continental Divide.

The highway shifts upward and we begin our ascent, climbing up at steepening angles along one side of the valley leading up to the pass. Downshifting through the range—fourth gear, third, sometimes even second—we eventually settle into a low-gear, slow-speed climb, Pass Creek coursing down the steep, rocky gorge. Higher and higher we climb, every curve revealing yet more elevation to be gained, engine thrumming, ears popping. Even our can of Pringles potato chips threatens to blow its freshness seal. Patches of snow grow larger and closer together until the ground is covered by the white stuff. Finally the grade lessens, the road gradually levels and we suddenly find ourselves at the summit of Wolf Creek Pass—10,850’ASL.

The highway shifts upward and we begin our ascent, climbing up at steepening angles along one side of the valley leading up to the pass. Downshifting through the range—fourth gear, third, sometimes even second—we eventually settle into a low-gear, slow-speed climb, Pass Creek coursing down the steep, rocky gorge. Higher and higher we climb, every curve revealing yet more elevation to be gained, engine thrumming, ears popping. Even our can of Pringles potato chips threatens to blow its freshness seal. Patches of snow grow larger and closer together until the ground is covered by the white stuff. Finally the grade lessens, the road gradually levels and we suddenly find ourselves at the summit of Wolf Creek Pass—10,850’ASL.

This is the Continental Divide, the very backbone of North America, rugged and raw and exposed. Like the peak of a roof, all lands east of here drain to the Rio Grande, Missouri, and Mississippi Rivers, eventually emptying into the Gulf of Mexico in the Atlantic Ocean. All parts to the west flow to the Colorado, Columbia, and other western rivers which pour themselves into the Pacific. At the top of the pass there is a vehicle turnout and a plaque marking the place.

This is the Continental Divide, the very backbone of North America, rugged and raw and exposed. Like the peak of a roof, all lands east of here drain to the Rio Grande, Missouri, and Mississippi Rivers, eventually emptying into the Gulf of Mexico in the Atlantic Ocean. All parts to the west flow to the Colorado, Columbia, and other western rivers which pour themselves into the Pacific. At the top of the pass there is a vehicle turnout and a plaque marking the place.

We pause here and disembark to stretch our legs, shoot snowballs at one another, and enjoy the moment. I notice that at one end of the turnout, the snowmelt trickles down the road back the way we came, while at the other end of the turnout, the meltwater runs down the pavement in the opposite direction, to the west. One single snowbank melting into two distant and separate oceans …

Clambering back in the van, we roll down the 7- and 8% grades on the western side of the summit road, descending into a beautiful mountain valley laced on both slopes with pines and aspen in full autumn color, and shortly after dark arrive in Durango, CO. Having spent the last few nights sleeping in the camper van at various campgrounds and Wal*Mart parking lots, we splurge a bit and take a room in a good hotel and enjoy dinner downtown before retiring.

Clambering back in the van, we roll down the 7- and 8% grades on the western side of the summit road, descending into a beautiful mountain valley laced on both slopes with pines and aspen in full autumn color, and shortly after dark arrive in Durango, CO. Having spent the last few nights sleeping in the camper van at various campgrounds and Wal*Mart parking lots, we splurge a bit and take a room in a good hotel and enjoy dinner downtown before retiring.

Day 4: Pueblo, Colorado

Over fresh-made huevos rancheros and breakfast burritos in a Mexican diner in Pueblo the next morning, we write postcards to friends and pore over our maps. Today we will turn westward and enter those mountains which until now have only been obscure and distant peaks growing ever larger on the horizon. Retracing our route of yesterday, we continue south on I-25, and swing off at Walsenburg to take Colorado State Hwy. 160 west into the Sangre de Cristo range of the Rockies. The stone-faced, snow-capped pyramids loom ever larger before us until the highway begins a long, winding climb. The engine temperature holds steady today and we soon find ourselves at the summit of North La Veta Pass—9413’ ASL. There is little time to enjoy the view, as the pavement quickly begins its descent and we pick up speed for the cruise downward.

Over fresh-made huevos rancheros and breakfast burritos in a Mexican diner in Pueblo the next morning, we write postcards to friends and pore over our maps. Today we will turn westward and enter those mountains which until now have only been obscure and distant peaks growing ever larger on the horizon. Retracing our route of yesterday, we continue south on I-25, and swing off at Walsenburg to take Colorado State Hwy. 160 west into the Sangre de Cristo range of the Rockies. The stone-faced, snow-capped pyramids loom ever larger before us until the highway begins a long, winding climb. The engine temperature holds steady today and we soon find ourselves at the summit of North La Veta Pass—9413’ ASL. There is little time to enjoy the view, as the pavement quickly begins its descent and we pick up speed for the cruise downward.

A unique set of climatic circumstances has created a singular place here: Great Sand Dunes National Monument. Westerly winds sweeping across this broad plain were once able to pick up and carry vast quantities of the fine sand which comprised its surface, until they came to the base of the Sangre de Cristo mountains. The wind raced upward on the western slopes but, unable to loft the sand up and over, dropped it at the foot of the mountains. Collecting here over several thousand years, the sheer volume of sand is incomprehensible, the dunes covering over 40 square miles and rising to 750’, the largest in North America. Though present conditions no longer deposit sand, the dunes are still relentlessly shaped and changed by the winds.

In the beautiful, newly redesigned campground we choose a nice cozy site bounded on one side by pinyon and juniper, with a view of the nearby dunes and the mountains on the other. Tawny mule deer traipse through the campsites, grazing on the greenery. After a quick lunch in camp we drive down to the trailhead and venture out onto the vast sand sheet at the foot of the dunes. The sheer immensity of the dunes is not truly appreciated until we have walked toward them, and walked, and walked, their golden waves and ripples and crests rising higher and higher to fill the sky before us.

In the beautiful, newly redesigned campground we choose a nice cozy site bounded on one side by pinyon and juniper, with a view of the nearby dunes and the mountains on the other. Tawny mule deer traipse through the campsites, grazing on the greenery. After a quick lunch in camp we drive down to the trailhead and venture out onto the vast sand sheet at the foot of the dunes. The sheer immensity of the dunes is not truly appreciated until we have walked toward them, and walked, and walked, their golden waves and ripples and crests rising higher and higher to fill the sky before us.

Later that evening around the campfire, the moon makes a brief appearance shortly after sunset, then chases the sun over the distant San Juan mountains. As the fire subsides to embers, a brilliant shooting star streaks across the darkened sky, east to west, trailing blue and green sparks that shimmer and almost audibly crackle. Perhaps it points the way to our continuing journey westward …

Copyright © 2024 All Rights Reserved