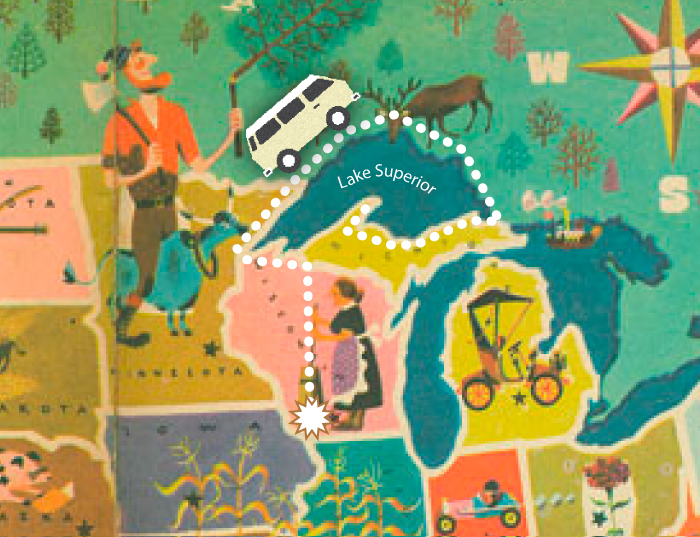

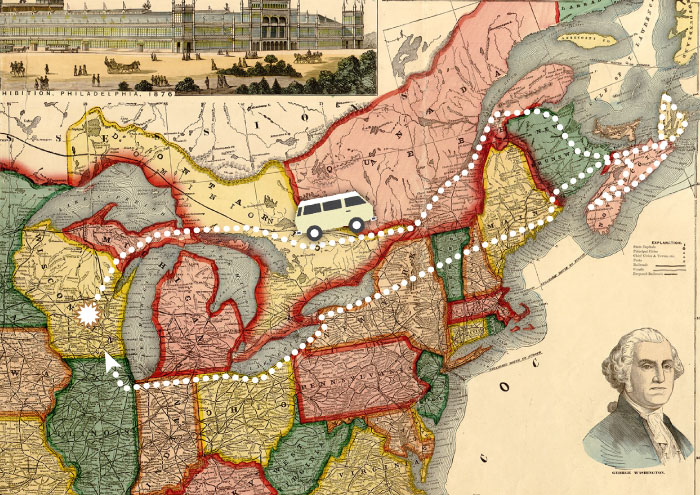

We recently returned from a four-week, 6800-mile Westfalia road trip from Wisconsin to the Pacific Northwest. We leisurely followed Highway 101 down the Pacific Coast through much of Washington and Oregon, then returned through John Day country and spent a few days in Yellowstone National Park.

We drive hard from Wisconsin and arrive at Badlands National Park about sunset. Before taking a site at Sage Creek campground we must carefully navigate a small herd of the native bovines. Note: a 2500-lb. bison has the right of way over a Vanagon.

An early start gets us over the Continental Divide at Homestake Pass, then on to the Missoula, Montana, KOA tonight, where a fellow Kamper™ arrives in a vintage GMC motor home towing a sweet Beetle.

At Kennewick, WA, we join the mighty Columbia River and opt to drive the northern bank rather than the more usual I-84 on the southern shore. The very lightly traveled Highway 14 follows the river down through stunning and ever-changing landscapes and ecosystems, sometimes high above the river, skirting around soaring basalt bluffs, and eventually entering deep forest near the Cascade Range.

We camp at Columbia Hills Historical State Park, a small but lovely campground right on the banks of the Columbia. Just a short hike away are several Native American petroglyphs which were saved from inundation when the nearby Dalles Dam was built.

We follow the Columbia River all the way down to where it empties into the Pacific, camping at Cape Disappointment State Park. Our site is just a few steps from the ocean, and only a mile from where Captain William Clark camped with a few of his men when the Lewis & Clark expedition arrived here in 1805.

The Lewis & Clark Interpretive Center sits on a decommissioned 1904 artillery battery, built to overlook and protect the harbor entry at the mouth of the Columbia River below.

Having arrived at the edge of the continent, I guess this is as far West as the Westy will be driving.

Exploring the backwoods of Leadbetter Point State Park.

Fortunately, the Westy requires no welding during this trip.

An afternoon at Heceta Beach reveals entire worlds thriving in the tide pools: anemones, sea stars, crabs, sea urchins, and more.

Our campsite near Florence, OR, offers a commanding view of the mouth of the Suislaw River; one afternoon a small pod of orcas swims up the river, hunting sea lions.

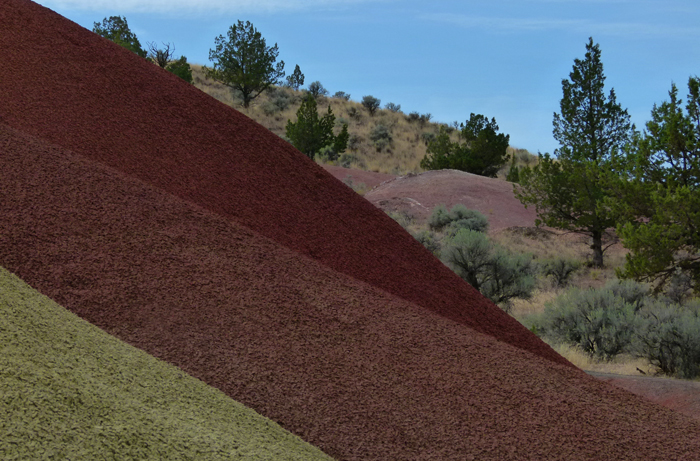

At John Day Fossil Beds National Monument, volcanic ash and other debris were laid down over millions of years, then eroded, leaving these colorful badlands.

The rusticated stone Roosevelt Arch at the north entrance of Yellowstone National Park, named for Theodore Roosevelt, who happened to be visiting the day the arch was begun and was asked to lay the cornerstone.

At Mammoth Hot Springs, geothermal-heated water travels underground through limestone, dissolving calcium carbonate, which then precipitates to form these hills of travertine.

The Yellowstone River roars through the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone.

The rugged terrain of the Park requires some advanced highway engineering.

At the head of the Grand Canyon, the Yellowstone River drops over 100 feet at Upper Falls.

A young grizzly cub learns from Mom how to dig for grubs.

Tiny Isa Lake, straddling the Continental Divide, drains into TWO oceans: the Pacific and the Gulf of Mexico. Either way, for the Vanagon, it’s all downhill from here …

A quick side trip through Grand Tetons National Park and Jackson Hole.

Homeward bound, the Rocky Mountains fade behind us.

We turn a few heads in Nebraska.

Our final night on the road, in a quiet Nebraska county campground …

Needless to say, this has gobbled up lots of farmland, hundreds of homes, highways, railroads, and other infrastructure, and is threatening to consume the city of Devils Lake. In recent years, more than 350 million in federal dollars have been spent to relocate people, raise roads, and build levees, and everywhere you look there are giant earthmovers and great piles of rip-rap. Side roads turn off and promptly disappear beneath the waves, standing forests of dead and blackened trees line the shallows, and abandoned farms poke up out of the water.

Needless to say, this has gobbled up lots of farmland, hundreds of homes, highways, railroads, and other infrastructure, and is threatening to consume the city of Devils Lake. In recent years, more than 350 million in federal dollars have been spent to relocate people, raise roads, and build levees, and everywhere you look there are giant earthmovers and great piles of rip-rap. Side roads turn off and promptly disappear beneath the waves, standing forests of dead and blackened trees line the shallows, and abandoned farms poke up out of the water.

At 8:30am we are awakened by the call of the open road, and by the sound of traffic already on it. After taking on fuel, food, and coffee we resume our journey. By mid-afternoon we arrive in the mile-high city of Denver. Being the gateway to the Southwest for those of us who live in the upper Midwest, we stay here only long enough to enjoy a walk on the 16th Street pedestrian mall, visit the lovely old Union Station, and share a chicken wrap at a sidewalk bench.

At 8:30am we are awakened by the call of the open road, and by the sound of traffic already on it. After taking on fuel, food, and coffee we resume our journey. By mid-afternoon we arrive in the mile-high city of Denver. Being the gateway to the Southwest for those of us who live in the upper Midwest, we stay here only long enough to enjoy a walk on the 16th Street pedestrian mall, visit the lovely old Union Station, and share a chicken wrap at a sidewalk bench.